What is a requirement? An excellent place to look for a definition is always a universally recognized dictionary. Too many times we redefine terms because we can, and then we end up adding to the plethora of definitions already in existence and thus contributing to further confusion.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a requirement as: “something essential to the existence or occurrence of something else”. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as: “A thing that is compulsory; a necessary condition”. When we, therefore, capture requirements, they are, by definition, compulsory. Failure of a solution to meet the specified requirements renders it, by definition, unacceptable.

We define requirements to meet a specific need or set of needs. These needs are used as the reference to determine if a requirement is indeed valid. A valid requirement addresses a need. Valid requirements, therefore, pin down (specify) the required, permitted and prohibited characteristics (functional and non-functional) of any solution to the need.

Can a need be invalid? No, by definition, needs add value for the stakeholder in accordance with what the stakeholder values. Stakeholders however quite often confuse their needs with wants, desires and even directed design and that makes it critically important to ensure that we understand the problem (what the stakeholder needs) before we try and capture requirements. The most common way of doing that is to capture a mutual understanding of the intended use of the system, often referred to as an Operational Concept Description (OCD) or a Statement of Operating Intent (SOI). That information provides the context we need to understand the problem, without which it is an utter waste of time trying to write requirements for a solution.

In the software domain, we often capture this statement of operating intent as user stories in the form: As a <user role>, I want to <activity>, so that <business value>. The user story is then typically accompanied by an acceptance criterion in the form: Given that <some pre-condition>, when <condition for action>, then <action>. A user story is however NOT a requirement – it states nothing about the required, permitted or prohibited characteristics of any solution, it merely states how the user intends to drive a solution.

So how do we distinguish between good requirements and bad requirements? There are quite a number of quality attributes that help us to define what is a good requirement. They include:

- Validity – adds (positive) net value

- Correctness – is factually correct

- Completeness – sufficiently complete (applies to requirements individually and as a set)

- Consistency – the absence of conflict within, and between, requirements

- Clarity – has syntax that is easily understandable by the intended reader

- Non-Ambiguity – there is a single semantic interpretation of the requirement

- Traceability – permits unambiguous requirements traceability in design and verification

- Verifiability – the requirement is such that (1) its satisfaction in the design is verifiable, and (2), its satisfaction in the implementation is verifiable

- Singularity – only one actor, one action and one object of action

- Feasibility – some means of satisfaction exists (applies to requirements individually and as a set)

- Balance – is optimum as a set (applies only to a set of requirements)

- Functional Orientation – oriented towards stating the problem, not directing the internal solution (applies only to a set of requirements)

- Freedom from Product/Process Mix – absence of process in a product requirement (with exceptions)

- Non-Redundancy – not duplicated within the set of requirements

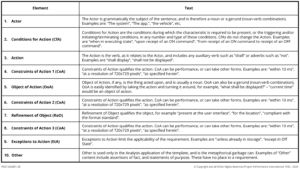

So how do we write a high-quality requirement? Project Performance International (PPI) employs a requirements parsing template as a framework for writing good requirements. The parsing template is defined in Table 1, with an example in Table 2.

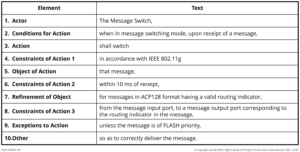

Table 1: PPI Requirements Parsing Template

Parse means break up into pieces and it is done in analysis on a phrase basis corresponding to the information content of the requirement. Only two pieces must always be present (actor and action) – up to nine pieces may be present (nine allowing for the fields that share pieces).

The illustration of the parsing template in Table 2 is one of the rare examples of all the elements of the parsing template being populated.

Table 2: Illustration of Elements of The Parsing Template