by

Martin Griffin

Leidos, Australia

Email: Martin.W.Griffin@Leidos.com

Abstract

The benefits of integrating systems engineering principles with project management philosophies are well established [Langley, M., Robitaille, S., & Thomas, J. (2011)]. Why then is it so difficult to achieve an integrated approach? How can we further strengthen and improve project and program success rates, particularly for complex projects?

The root cause of this dilemma appears to lie in the historic evolution of two lifecycle-delivery methodologies (program/project management [PM] and systems engineering [SE]) – the representative industry bodies and the resulting suite of discipline standards and respective bodies of knowledge began diverging in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Even though both of these communities had a common mission and overall goal (and to this day still do), the evolutionary development of their processes and tool-sets have led to individuals within both communities not fully understanding the other’s domain and not creating a program environment that fosters success. Compounding this unfortunate development, a divergence concerning conflicting mindsets in organizational silos have created in many programs a barrier to cooperation, resulting in ‘unproductive tension’ as documented in PMI and INCOSE studies that were performed during the research phase of the book (2011 to 2014). There are well described in the book, Integrating Program Management and Systems Engineering [Eric Rebentisch, Editor-in-Chief (2017)].

This paper explores the history of both project management and systems engineering, in order to uncover the aspects causing continuing conflicts and to highlight where and why the elements of project delivery struggle to align and quite often cause friction. Based on this understanding, the various studies and research comparing these two disciplines is explored to understand why the integration of these methodologies is prerequisite to success.

Practical approaches are presented to resolve the barriers to integration and actions to achieve maximum value for all stakeholders are described.

Copyright © 2018 by Martin Griffin. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Since the inception of modern project management practices in the 1960’s (having origins in the Critical Path Method), the evolution and worldwide adoption of its underpinning theorems and processes have resulted in a standardized approach to project delivery within organizations across the globe. Its popularity and to a large extent necessity, through the 1970’s global recessions actually resulted in significant corporate restructures in the 1990’s to ensure maximum resource alignment into project-based teams to focus individual’s efforts to the realization of organizational benefit from its Project Portfolio. This has meant the formation of specific roles skilled in the various knowledge areas of project management even though these have not been formally recognized technical disciplines within academia. The current day project manager will have a broad range of technical skill sets ranging from technical trades to engineering and even business management. This evolutionary development has largely resulted in prescriptively defined role responsibilities with the accountability of financial or executive authority from the organization to deliver a defined scope within the constraints of time, cost, and quality.

Similarly, the ‘science’ and practice of systems engineering has evolved from the 1940’s where the principles were being deployed in early telecommunications development (Bell Laboratories) and then heavily utilized within NASA and the US Defense agencies in the 1950’s and 60’s, when these organizations developed their own detailed processes across the full life cycles of projects and programs. The resulting perceptions led to systems engineering being relegated to complex system development and being constrained to practitioners from technical disciplines. The principles did continue in most sectors including automotive, transportation, and mining; however, they were heavily customized and disassociated from the systems engineering origins. So, even though the two philosophies of Project Management and Systems Engineering have the same mission with the same underlying gated constructs, their respective evolutions diverged to such a magnitude that the practitioners in each do not understand the terminology and nomenclature of the other.

This was recognized by the representative Industry bodies PMI and INCOSE and in 2011 these groups came together to study and understand the ‘unproductive tension’ that was being associated with project failures. The research, which ran over multiple studies through to 2014, highlighted that a principle cause was the key roles of the Project Manager and the Chief Systems Engineer did not understand each other’s methodologies. This work was captured in the book ‘Integrating Project Management and Systems Engineering’, Eric Rebentisch of MIT Editor-in-Chief and published in 2017. This work surmises that further education of the key project roles to better understand the others lifecycle processes would improve the integration and therefore yield better collaboration leading to more positive project outcomes.

The research findings and recommendations of this industry body collaboration are symptomatic of the divergent evolution that these project delivery methodologies have experienced since the 1970’s. This paper will highlight the human nature aspects of this mindset divergence and provide some practical approaches to bridging the divide and maximizing the value inherent in aligning these lifecycle delivery frameworks.

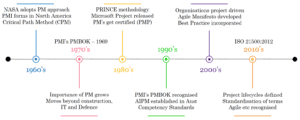

Project Management Evolution

There are a plethora of texts and papers on the origins and the subsequent evolution of modern day project management, and anyone interested in the detailed breakdown of this history can refer to the Project Management Institutes (PMI) list of references or the 2004 PMI Research Conference paper by Aaron Shenhar [Shenhar, A. & Dvir, D. (2004). Project management evolution] which has a good breakdown of the underpinning concepts as they appeared and were further refined through the decades. As a comparative breakdown of the key turning points for Project Management as a philosophy and resulting methodology the Timeline in Figure 1 is sufficient to describe the evolution:

Figure 1 : Project Management Evolution Timeline

Some texts point to the late 1950’s as the origins when the efforts to develop complex weaponry and warfighting systems required detailed planning and business collaboration, but regardless of the driving influence, the predominant factor concerning the emergence of the current principles was in the release of the Critical Path Method (CPM) for activity scheduling and the subsequent Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) charts. These techniques were readily adopted by the larger organizations such as NASA as a means to manage the complicated aspects of the internal and external organization activities needed to deliver their developmental programs. With the rapid uptake of these management techniques came a need to capture best practice and industry standards to enable the supporting organizations to deliver into these complicated programs; this resulted in the formation of the PMI in North America. This group formed a charter with a focus on collating and disseminating industry best practice and lessons learned, and this was captured within the PM Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) which was officially released as a published resource in 1969.

Through this same period, other organizations were developing and administering internal models based on similar application of tools. One which has risen to world-wide adoption is the PRINCE methodology which originated in the UK as the Project Resource Organization Management Planning Techniques (PROMPT) and was primarily adopted by the Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA) who renamed it PRINCE, “PROMPT II IN the CCTA Environment” and which subsequently became known as “PRojects IN Controlled Environments”. The current version, PRINCE II, has become the pseudo-defacto methodology for most professional Project Managers and preferred by the majority of industries and organizations around the globe.

During the 1970’s, with the global recessions, the constraint of cost led to the project management principles becoming increasingly important in order to survive, and its popularity spread to most other industry sectors. With this came the need for better control, and as technology in the electronics space was making computers more accessible and reliable into the 80’s, tools such as Microsoft Project which embedded the scheduling techniques became the default for managing projects. In the 1990’s the industry bodies assumed a more prescriptive stance and driven by the desire to increase membership and the need for more auditable process (driven by ISO9001 Quality standards development), established “Competency Standards”, against which practitioners were measured to assess understanding of the underlying principles and technique application.

Into the 2000’s, the prescriptive standards-driven approach led to organizations restructuring to provide clarity between everyday project operations and the teams responsible for improvement of operations or establishment of a new product stream or development of solutions into other operational organizations. Several notable project failures, and a growing perception that ICT projects regularly exceeded planned schedules, identified a need for more flexibility within complicated programs running over multiple years and the Agile Manifesto was developed to enable breaking larger programs into smaller manageable but linked projects.

The period through the 2010’s has seen very little change to the fundamentals of Project Management as detailed within the standards PMBOK and PRINCE II and brought more refinement and more efficient tools with 2017 seeing the formal adoption of Agile within the PMBOK process set and the Earned Value Management aspects tightening up on Earned Schedule as a means to control project over-runs. The current embodiment of Project Management has seen an entire supporting resource construct evolve where individuals are purely skilled within one element of Project Management such as Project Controllers and Planners and Project Management Office (PMO) roles and responsibilities becoming standardized throughout industry.

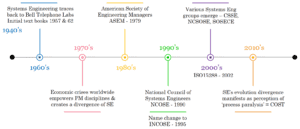

Systems Engineering Evolution

Similar to the PM evolution, there is some variance in opinions as to the original surfacing of the systems engineering methodologies, and for those interested in exploring this you should refer to INCOSE for useful reference texts. However, the more common view is that the processes used in modern day systems engineering originated within Bell Laboratories during the 1940’s for development of complex telecommunications systems. The timeline below shows the parallel path of this lifecycle delivery methodology.

Figure 2: Systems Engineering Evolution Timeline

The first texts that introduced the concepts of ‘Systems Thinking’ were published approximately in 1960, and given the coincidence with the Space Race and the Cold War, rapid emergence of technologies remained dominant on the global stage. The Department of Defense and NASA were very early adopters of these techniques and principles. With limited documented information on how to apply this approach these two agencies established their own internal models and organizational rules and these progressively became the ‘standards’ adopted across businesses supporting these entities and then out to adjacent market sectors where strict control of research and development was needed to assure the validity of the original operating need or organizational goal.

From its very original introduction the intent of Systems Engineering was to establish robust planning of the various developmental stages of a product or systems lifecycle to show the traceability of an operational need through to the implemented system in operation with consideration of subsequent lifecycle phases including disposal/replacement. With the initial sectors that adopted and developed these techniques there was an early and persistent perception that it was expressly for the complex and complicated developmental environments and also the perception that these areas could afford the additional planning and administrative burden inherent in the Military Standards (MIL-STD) and NASA processes for high criticality software and safety critical applications.

In the 1970’s the tight cost controls required led to the reduced uptake of Systems Engineering and in the industries that had incorporated some of the principles such as automotive manufacturing the use of LEAN and Six Sigma cost minimization techniques refined the use of Systems Engineering to a point that it was no longer recognizable against the mainstream definitions. In 1979 a group of Engineering Managers, American Society of Engineering Managers (ASEM), formed to foster and promote the use of Systems Engineering. This led to a resurgence of the discipline and wider adoption where assurance for safety critical systems was needed and by the 1990’s the National Council of Systems Engineers (NCOSE) had formed as the industry body responsible for the discipline competency standards and owner of the SE Body Of Knowledge (SEBOK). By 1995 other similar industry associations around the world (including SESA) agreed to collaborate with NCOSE and the group was renamed as INCOSE (International). During this period the US Department of Defense decided to reduce their administration costs associated with maintaining the MIL-STD set of processes in preference to adopting the INCOSE managed suite of standards giving rise to the need for an International Standards Organization (ISO) release for the discipline which officially occurred in 2002.

With the advancement of technologies allowing more complex and complicated systems to be developed, streams of Systems Engineering emerged focused on Complex Systems and System of Systems with complimentary industry associations (CSSE, NCSOSE and SOSECE). This has further exacerbated the perception that the methodology is associated with high technology development programs and led to a universal belief that the discipline has high cost of implementation and it can only be warranted on these programs that can absorb this cost burden. In a self-actualization way the Systems Engineering processes and tools developed for application on high complexity programs tended to get deployed by practitioners engaged in the other industry sectors (e.g. defense processes being used within the transport sector) which acted to substantiate business leaders’ views of limited value in adopting the methodology on general system design work.

The Common Goal

Is there a fundamental difference between the methodologies of Project Management and Systems Engineering, or are these simply two approaches to achieving the same organizational goals? The answer exists in some of the research work undertaken by the PMI-INCOSE-MIT alliance [Conforto et al. (2013)] and can also be seen in the fundamental mission statement of the two approaches.

Project Management Mission:

The application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements.

Systems Engineering Mission:

Assure the fully integrated development and realization of solutions which meet stakeholders’ expectations within cost, schedule, and risk constraints.

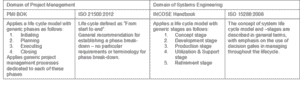

The following table shows the comparison of the primary PM and SE standards.

Figure 3 : Comparison of the Objectives of PM and SE from the Respective Standards

Figure 3 : Comparison of the Objectives of PM and SE from the Respective Standards

From Figure 3 it is clear that both domains are based on a lifecycle delivery model that segments the activities into a time-phased breakdown of work scope needed to develop and implement the solution. The more significant difference observed within the industry body handbooks is that INCOSE has a focus on development whereas the PMI BOK provides more generic phase segregation. A further difference can be seen in the timeframe over which the processes get deployed with Systems Engineering clearly showing the decisions needing to consider the full lifecycle to retirement, but Project Management is more contractual in nature applying until the completion of the project scope.

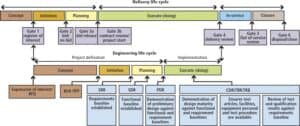

So, at a fundamental level these two methodologies are attempting to achieve the same goal and even with a similar time-phased deconstruction of the constituent activity elements. The differences stem more from the areas of application and how the member communities and representative industry bodies have articulated the processes within guides and standards. Overlaying the phases and key activity gates between the two it becomes apparent that there is also an organizational perspective at play where PM assumes a contractual management responsibility and relegates the SE administration to the technical aspects of the contracted scope. When viewing the traditional PM and SE lifecycle phases as shown in Figure 4, it is clear that the Requirements Baseline is referring to technical requirements and the Functional Baseline is the required performance of the technical elements. The contractual and other project delivery requirements are not managed in the same way which regularly leads to issues of scope control and deviations to contract terms.

Figure 4: Traditional representation of phases and review gates

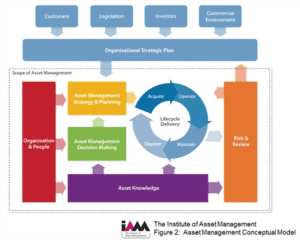

This ‘pigeon-holing’ of the respective methodologies driven by standards and organizational constructs is not constrained to these two methodologies as the same can be seen in the newer organizational management technique of Asset Management which has risen to cover an operational need to more effectively manage the resulting capabilities from projects.

Figure 5 : The IAM Asset Management Conceptual Model

The Asset Management (AM) methodology actually overlaps Project Management (or more often Portfolio Management) and Systems Engineering and introduces another suite of processes that need to be managed within an organization (refer Figure 6). With the increasing popularity of this more recent methodology another organizational construct is emerging and additional internal interfaces and commensurate duplication of process is emerging.

For the purposes of this paper it is important to recognize that methodologies and related processes must be viewed as enablers for project delivery and organizational value and not drivers to achieve compliance under a Quality Management regime. In the case of Asset Management, the ‘activity’ of Systems Engineering has been diminished in applicability to a sub-element of Lifecycle Delivery as can be seen highlighted in Figure 6 below. This has a subsequent connotation that to attain ISO55000 (AM) accreditation the scope of System Engineering will be constrained to initial or subsequent Asset creation and that Project Management is only required where the Lifecycle Delivery meets the organizations definition of a ‘Project’.

Figure 6 : The IAM Asset Management Process Elements

Figure 6 : The IAM Asset Management Process Elements

Research into the Value of adopting SE

For the last two decades the resurgence of Systems Engineering has attracted significant research effort into understanding the value of its adoption. Most of this research has centered on the industries that have historically adopted and implemented Systems Engineering such as Defense and NASA and a significant amount has been sponsored by the representative industry bodies such as INCOSE [Eric Honour – 2002 through to 2010]. However more recent activity is exploring the value gained across other industry sectors such as Health and Transport but the context tends to be related to the increasing complexity within the systems deployed in these sectors.

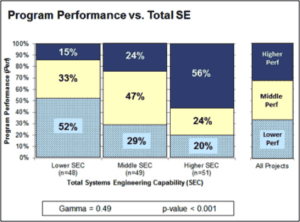

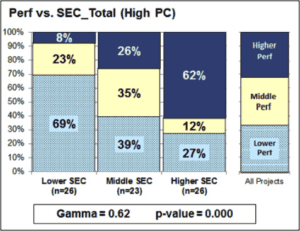

A study conducted by Carnegie Melon University in 2012 [Elm, J., Goldenson, D (2012)] and repeated in 2014 explored the relationship between successful project outcomes and the extent of Systems Engineering employed within the organizations. The first study was predominantly in the software domain and heavily Defense-centric but the results were quite conclusive and so the study was repeated extending out into other sectors and across a broader industry base with essentially the same results. Figure 7 below shows the outcome with organizations having higher SE usage showing significantly higher performance across their projects. This study further looked at project complexity and found a further correlation of high performance with high deployment of SE (Figure 8).

With the research undertaken by the PMI and INCOSE alliance there is compelling evidence to warrant serious consideration of integrating SE into any PM lifecycle delivery model. The challenge is how to do it within the current segregated discipline environments and the heavily engrained organization structures across most industry sectors.

Figure 7 : Carnegie Mellon University Study into Project performance and SE

Figure 8 : Carnegie Mellon University Study looking at Project Complexity

The Root Cause of Poor Integration

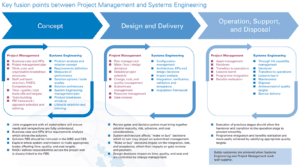

The PMI-INCOSE research identified a common theme of ‘Unproductive Tension’ within projects and organizations where there were performance issues. There were a number of potential causes identified from lack of understanding between the two domains to direct conflict of role objectives and obligations, but the end result was project churn and difficulty in delivering an acceptable outcome. One aspect of this research that was overlooked was that of domain boundaries and the resulting constrained thinking. A recent output of the research has been some integration guides produced in the UK (Figure 9) which demonstrate a view of responsibility boundaries within the two disciplines. Within current organization structures this view provides a means to enable integration conversations to occur and hopefully initiate some effective collaboration however it also perpetuates the present perception that SE is constrained to the technical aspects of the project.

Figure 9: Guide Z11 Issue 1.1, Jan 2018 – INCOSE UK & Project Management

If you explore the ten knowledge areas associated with PM as described within PMBOK and shown in the mind map of Figure 10 you find every element is addressed within the SE methodology and this approach actually permits the inter-relationships between each area to be assessed against the operational need or desired capability outcome. The same can also be said for the Asset Management aspects of Figure 6 within and outside of the Lifecycle Delivery aspect.

Figure 10: The Knowledge Areas of Project Management Responsibility

Therefore, the true root cause of poor integration is actually ‘constrained thinking’; the following list of integration issues give rise to this cause and need to be explored within any organization if an enduring integration is to be realized:

Human Nature: Conditioned or Local Mindsets

Communication: Speaking a different language

Culture: Process Compliance – Resistance to Change

Environment: Industry norms – e.g. Rail Standards

Societal: Business practices – Contracting methods

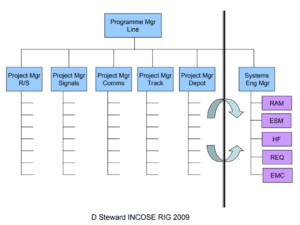

Organizational: Organization structure with Role definitions

The Organization Breakdown Structure (OBS) issue is actually a prevalent one that can readily bring rise to the other issues listed and one that gets influenced quite often by the single view-point of project management. This has evolved since the 1970’s and is quite evident in certain industry sectors but in reality exists across all industry sectors. The following representative organizational construct is often seen within the rail industry where a scope constrained view leads to a perception that Integrated Project Teams (IPT) based around the technical packages is an effective OBS. This approach regularly leads to silos where each technical group drives their solution in isolation to the other interdependent system aspects and inevitably the rolling stock arrives on schedule for testing, the infrastructure including signaling is delivered to schedule and the depot gets commissioned on time, but nothing actually integrates and each element becomes a constraint requiring compromise of the total capability.

Figure 11: Common Organization Structure in the Rail Industry

Actions Needed to Further Strengthen and Improve Integration of PM and SE

Chapter 16 of Integrating Program Management and Systems Engineering (IPMSE) provides calls to action for several groups of stakeholders: academia, enterprise, policymakers, industry and professional societies, and researchers. These calls to action identify specific actions that stakeholders in each group should take.

This Newsletter, Project Performance International Systems Engineering Newsletter (PPI SyEN), has provided a series of articles over the past eighteen months (PPI SyEN 54 [June 2017] through PPI SyEN 71 [November 2018]) (see https://www.ppi-int.com/syen-newsletter/ for copies of these issues of PPI SyEN) that provide an introduction to the critical concerns and a summary of each of the chapters of IPMSE as well as many specific recommendations, particularly for systems engineers.

From my own experience and perspective, following are several actions that need to be “worked” aggressively if we are to avoid continued failures of complex projects and programs:

- Professional Societies such as INCOSE and PMI need to actively engage with the Commonwealth of Australia and other end customer organizations to highlight the importance of not over-prescribing Standards compliance within their Contractual models.

- Academia needs to acknowledge the impact of societal business constructs on how projects get managed and delivered to ensure new graduates are equipped to enter industry and operate within any organization’s process frameworks.

- CEO’s and business leaders need to recognize the human nature aspects of the various disciplines required to effectively deliver on their company visions and strategies and ensure that delivery models seek to optimize the benefits from discipline tools rather than prescribing compliance to them.

- Practitioners of any given discipline or within any developed business process construct need to be consciously aware of the human characteristic of ‘conditioned thinking’ that inhibits innovation and artificially constrains our ability to reason. The processes and tools at our disposal were likely created by others for an outcome not suited to the current objective.

A summary note to all of the systems engineering practitioners: constraints and interfaces are what the systems engineering methodology is ideally structured to manage. It is critically important to understand that this not be limited to the technical elements of any project. In order to effectively deliver on the systems engineering mission, the full set of engaged disciplines on any given project need to be included, and the silos and barriers that exist at any stage within a lifecycle need to be understood and addressed in order to yield productive integration.

Transition to an Enduring Integrated Model

There is no ‘one size fits all’ answer, but wherever it is possible to change the organization structure or the business processes (even through tailoring), then this should be the starting point. The ‘Unproductive Tension’ identified by PMI-INCOSE and the ‘Constrained Thinking’ highlighted earlier both have significant foundation within the organization construct and the segregation of delivery streams (usually manifested in processes adopted). Utilizing SE principles to understand the operational (or organizational) need and then creating a process model that is optimized to deliver that need in an integrated team of multi-disciplined resources (including all required disciplines outside of the technical/engineering domain) all working under a common goal to deliver the capability required (not just the scope of work).

Concerning organizational restructuring, this needs to occur relative to the project or business outcome to be achieved and it is not simply forming a ‘line-management’ structure for grouping of disciplines. The structure needs to follow the Product Breakdown Structure (PBS) so that the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) does not inherit artificial organizational interfaces caused by resource silos. There is usually resistance to significant re-arrangement of the ‘deck-chairs’ within a company; however, the businesses that can foster this adaptive and flexible culture can remain current, relevant, and innovative, which in today’s disruptive environment translates to growth.

Concerning the lifecycle delivery processes, the approach needs to follow a similar logic whereby a single coherent set of processes is adopted that matches the work to be undertaken. It is extremely important that the processes do not get associated with any discreet element of the organization; otherwise, responsibility and accountability become diluted and finger-pointing arises. A common example is the PM delegating responsibility for system reviews to the engineering team because they are associated with ‘engineering reviews’. Even if the entire scope of the system review is technical in nature, the intent of the review is to establish a project maturity level and residual risk to carry forward, so it will always require the entire team’s involvement and will impact every element of the PM Knowledge Areas.

Therefore, achieving a fully integrated approach requires breaking down the mindsets associated with decades of standards adoption, and establishing an integrated organization structured to optimally achieve the outcome, and working to a single cohesive lifecycle delivery process tailored to suit the level of complexity, as well as balancing the totality of risk in a collaborative manner with ownership specifically where the risk can be effectively controlled and mitigated. If working within constraints of large inflexible organization constructs and rigid customer contractual obligations, then the bare minimum is to ensure elimination of silos, an unwavering focus on the outcome (i.e., the capability required) and avoidance of compliance thinking to permit sufficient cross-pollination of the PM and SE principles to avoid ‘unproductive tension’.

References

Boehm, Barry, Ricardo. Valerdi, and Eric Honour. 2008. “The ROI of Systems Engineering: Some Quantitative Results for Software-Intensive Systems.” Systems Engineering, Volume 11, Issue 3 (Fall 2008), pp. 221-234. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sys.20096.

Conforto, Edivandro, Monica Rossi, Eric Rebentisch, Joseph Oehman, and Mari Pacenza. (2013). “Improving the Integration of Program Management and Systems Engineering”. Whitepaper presented at the 23rd INCOSE Annual International Symposium, Philadelphia, USA, June 2013. Available here.

Elm, Joseph P. and Dennis R. Goldenson, “The Business Case for Systems Engineering Study: Results of the Systems Engineering Effectiveness Survey”. Special Report, CMU/SEI-2012-SR-009 (November 2012). Available at https://resources.sei.cmu.edu/asset_files/SpecialReport/2012_003_001_34067.pdf.

Honour, Eric. 2003. “Toward An Understanding of the Value of Systems Engineering.” Proceedings of the First Annual Conference on Systems Integration, Stevens Institute of Technology, March 2003, Hoboken, NJ, USA. Available at https://www.bing.com/search?q=Honour,+E.C.+%E2%80%9CToward+Understanding+the+Value+of+Systems+Engineering&src=IE-SearchBox&FORM=IESR4A&pc=EUPP_UE04.

Honour, Eric. “Understanding the Value of Systems Engineering,” INCOSE International Symposium, Toulouse, France, June 20-24, 2004. Volume14, Issue1. Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.2334-5837.2004.tb00567.x.

Langley, Mark, Samantha Robitaille, and John Thomas. (2011). “Toward a new mindset: bridging the gap between program management and systems engineering”. Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2011—North America, Dallas, TX. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. Available at https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/bridging-gap-program-management-systems-engineering-6213.

Rebentisch, Eric, Editor-in-Chief. (2017). Integrating Program Management and Systems Engineering – Methods, Tools, and Organizational Systems for Improving Performance. Hoboken, New Jersey USA: John Wiley & Sons. Available at https://www.amazon.com/Integrating-Program-Management-Systems-Engineering/dp/1119258928/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1541851462&sr=1-2&keywords=rebentisch.

Shenhar, Aaron and Dov Dvir. (2004). Project management evolution: past history and future research directions. Paper presented at PMI® Research Conference: Innovations, London, England. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. Available at https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/project-management-evolution-research-directions-8348.

Steward, David (Parsons Brinckerhoff Ltd) 21st January 2009 INCOSE UK Rail Interest Group. Available at http://www.incoseonline.org.uk/Documents/Groups/Railway/RIG_0901_January.pdf.

About the Author Martin has over 20 years’ experience in engineering design and management, with the recent 10 years specifically within the Maritime Defense sector. He has eight years’ experience as an Executive Engineering Manager and is a discipline specialist in Systems Integration Engineering, Maritime and Mechanical Engineering, RAM Analysis, Safety Cases, and Risk and Issue Management. Martin is experienced in the successful delivery of complex engineering systems and services within Technical Regulatory Frameworks in the defense sector.

Martin has over 20 years’ experience in engineering design and management, with the recent 10 years specifically within the Maritime Defense sector. He has eight years’ experience as an Executive Engineering Manager and is a discipline specialist in Systems Integration Engineering, Maritime and Mechanical Engineering, RAM Analysis, Safety Cases, and Risk and Issue Management. Martin is experienced in the successful delivery of complex engineering systems and services within Technical Regulatory Frameworks in the defense sector.

Martin has worked in project management capacities as well as engineering management, and has led organizational change initiatives to maximize the effectiveness of delivery. Through the 2009 Defense Strategic Reform Program, he molded a functionally based engineering group into a LEAN project delivery team operating across individually tailored Systems Engineering upgrades, to halve the cost base of the organization. More recently, he led the restructuring of engineering disciplines into multi-domain delivery cells that are able to operate across multiple support contracts utilizing unique system engineering process models.